OAuth 2.0

- OAuth 2.0

- TODO

- What Is OAuth?

- Example

- How does OAuth solve the password anti-pattern?

- How does OAuth help users interact with APIs on the backend?

- How does this benefit the API application developers?

- OAuth Central Components

- Security and the Enterprise

- OAuth is not an Authentication Protocol

- OAuth 2.0 Summary

OAuth 2.0

“The OAuth 2.0 authorization framework enables a third-party application to obtain limited access to an HTTP service, either on behalf of a resource owner by orchestrating an approval interaction between the resource owner and the HTTP service, or by allowing the third-party application to obtain access on its own behalf.”

TODO

- https://cloud.google.com/apigee/docs/api-platform/security/oauth/oauth-introduction

- https://www.fortinet.com/resources/cyberglossary/oauth

- https://auth0.com/intro-to-iam/what-is-oauth-2

What Is OAuth?

https://developer.okta.com/blog/2017/06/21/what-the-heck-is-oauth#what-is-oauth

To begin at a high level, OAuth is not an API or a service: it’s an open standard for authorization and anyone can implement it.

More specifically, OAuth is a standard that apps can use to provide client applications with “secure delegated access”. OAuth works over HTTPS and authorizes devices, APIs, servers, and applications with access tokens rather than credentials.

There are two versions of OAuth: OAuth 1.0a and OAuth 2.0. These specifications are completely different from one another, and cannot be used together: there is no backwards compatibility between them.

Which one is more popular? Great question! Nowadays, OAuth 2.0 is the most widely used form of OAuth. So from now on, whenever I say “OAuth”, I’m talking about OAuth 2.0 – as it’s most likely what you’ll be using.

Example

OAuth, or open authorization, is a widely adopted authorization framework that allows you to consent to an application interacting with another on your behalf without having to reveal your password. It does this by providing access tokens to third-party services without exposing user credentials.

OAuth’s main value is that it provides applications with secure designated access so that users can engage with the secure portions of a website without the need to create a new account with new credentials.

Let us say you want to tweet a story you are reading on CNN.com. When you click on the tiny blue bird icon on the CNN.com article’s webpage, a window will pop up asking you to log in to Twitter. By logging in to Twitter at that moment (or perhaps you are already logged in), you are telling Twitter that it is okay for CNN.com to post on your Twitter feed without providing CNN.com your Twitter password.

This is not only convenient but also prudent because you do not need to create an account with CNN.com just to post to Twitter. Additionally, should CNN.com experience a breach, your Twitter password remains safe.

Instead of sharing password data, OAuth uses authorization tokens to prove an identity between consumers and service providers, such as Twitter, Facebook, and Google. Most users are blissfully unaware of what is going on in the background. As such, from a user experience perspective, OAuth delivers much-needed functionality for users needing to engage with different services that require sign-on.

How does OAuth solve the password anti-pattern?

Or, “Why OAuth?”

https://developer.okta.com/blog/2017/06/21/what-the-heck-is-oauth#why-oauth

OAuth was created as a response to the direct authentication pattern. This pattern was made famous by HTTP Basic Authentication, where the user is prompted for a username and password. Basic Authentication is still used as a primitive form of API authentication for server-side applications: instead of sending a username and password to the server with each request, the user sends an API key ID and secret. Before OAuth, sites would prompt you to enter your username and password directly into a form and they would login to your data (e.g. your Gmail account) as you. This is often called the password anti-pattern. See https://arstechnica.com/information-technology/2010/01/oauth-and-oauth-wrap-defeating-the-password-anti-pattern/

To create a better system for the web, federated identity was created for single sign-on (SSO). In this scenario, an end user talks to their identity provider, and the identity provider generates a cryptographically signed token which it hands off to the application to authenticate the user. The application trusts the identity provider. As long as that trust relationship works with the signed assertion, you’re good to go. The diagram below shows how this works.

How does OAuth help users interact with APIs on the backend?

https://developer.okta.com/blog/2017/06/21/what-the-heck-is-oauth#oauth-and-apis

A lot has changed with the way we build APIs too. In 2005, people were invested in WS-* for building web services. Now, most developers have moved to REST and stateless APIs. REST is, in a nutshell, HTTP commands pushing JSON packets over the network.

Developers build a lot of APIs. The API Economy is a common buzzword you might hear in boardrooms today. Companies need to protect their REST APIs in a way that allows many devices to access them. In the old days, you’d enter your username/password directory and the app would login directly as you. This gave rise to the delegated authorization problem.

“How can I allow an app to access my data without necessarily giving it my password?”

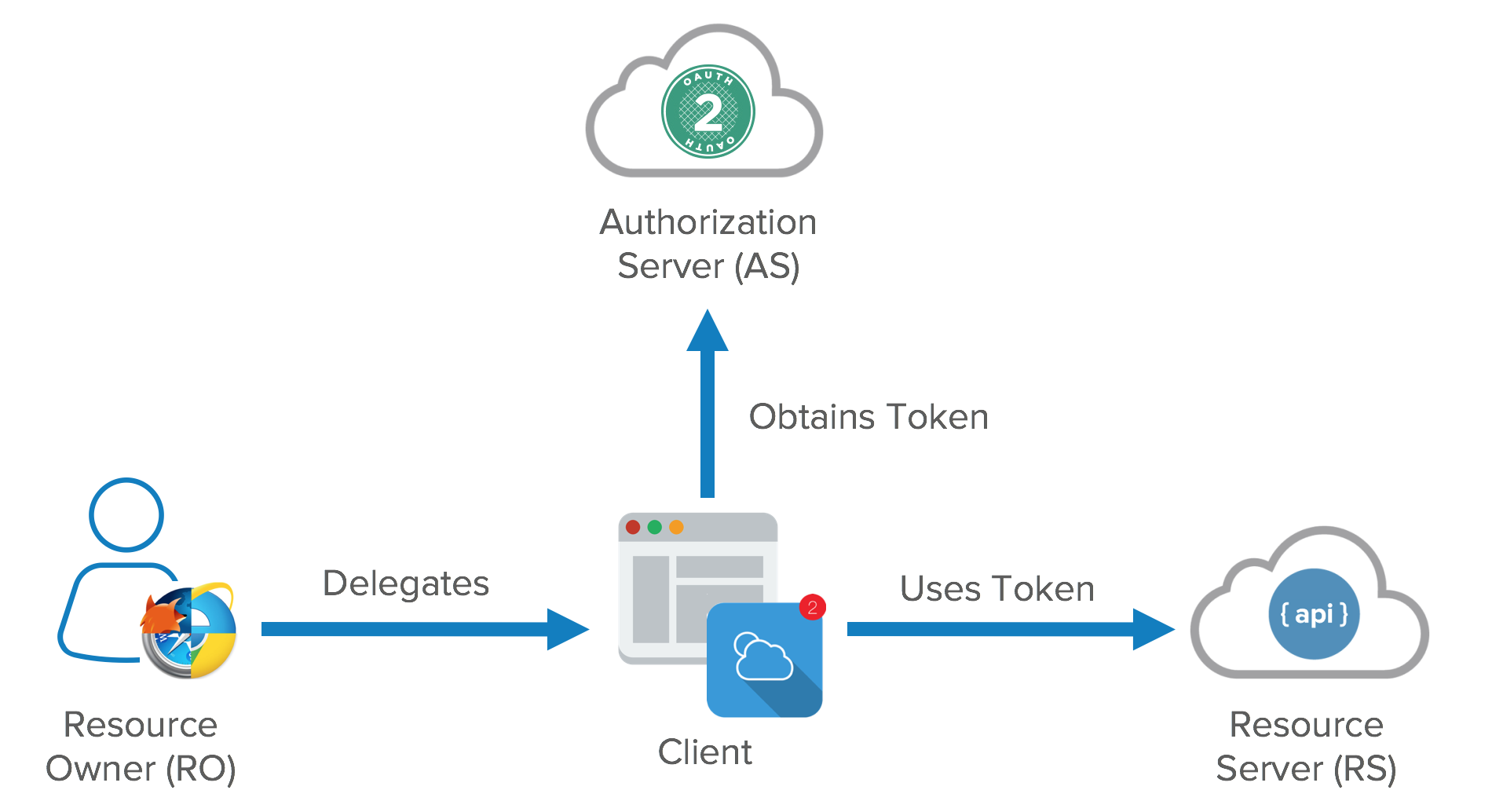

OAuth is a delegated authorization framework for REST/APIs. It enables apps to obtain limited access (scopes) to a user’s data without giving away a user’s password. It decouples authentication from authorization and supports multiple use cases addressing different device capabilities. It supports server-to-server apps, browser-based apps, mobile/native apps, and consoles/TVs.

You can think of this like hotel key cards, but for apps. If you have a hotel key card, you can get access to your room. How do you get a hotel key card? You have to do an authentication process at the front desk to get it. After authenticating and obtaining the key card, you can access resources across the hotel.

To break it down simply, OAuth is where:

- App requests authorization from User

- User authorizes App and delivers proof

- App presents proof of authorization to server to get a Token

- Token is restricted to only access what the User authorized for the specific App

How does this benefit the API application developers?

When you are using OAuth, you outsource user authentication and authorization to a central identity provider (IdP). Users sign in to the IdP and are granted time-bound permissions in the form of an access token. This token is presented to other applications, APIs, and services.

Using such a centralized service has a number of advantages:

- One system holding user PII can be locked down and protected more easily than many systems.

- Just as a database is focused on retaining data with certain guarantees, an IdP can focus on login functionality and provide a well understood interface.

- Because an IdP is the place where authorization and authentication decisions are performed, it becomes a single central location for analyzing, enabling, and disabling access to systems.

- When all users authenticate at the IdP, you can easily add functionality, such as federation to other identity sources or security measures like multi-factor authentication. All applications, APIs and services which accept tokens from the IdP benefit from additional functionality without any change to their code.

OAuth, having been around for over a decade, is ubiquitous. There are OAuth clients in almost every modern programming language, and even some less modern ones such as COBOL. This ubiquity means that when you are working with an OAuth server, you can leverage libraries to perform the integration quickly.

OAuth Central Components

https://developer.okta.com/blog/2017/06/21/what-the-heck-is-oauth#oauth-central-components

OAuth is built on the following central components:

- Scopes and Consent

- Actors

- Clients

- Tokens

- Authorization Server

- Flows

OAuth Scopes

https://developer.okta.com/blog/2017/06/21/what-the-heck-is-oauth#oauth-scopes

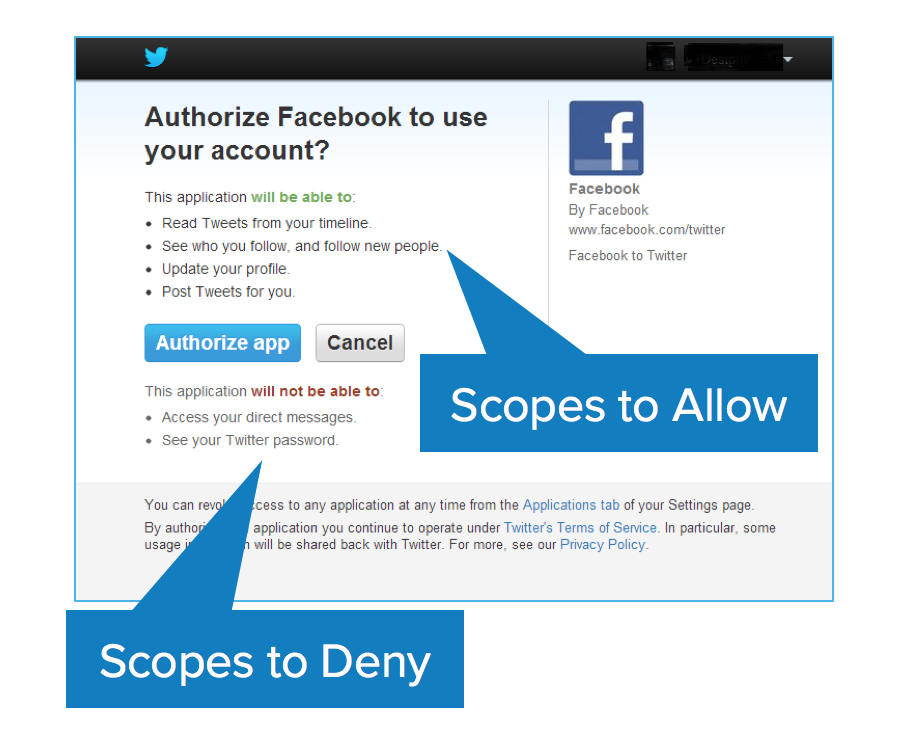

Scopes are what you see on the authorization screens when an app requests permissions. They’re bundles of permissions asked for by the client when requesting a token. These are coded by the application developer when writing the application.

Scopes decouple authorization policy decisions from enforcement. This is the first key aspect of OAuth. The permissions are front and center. They’re not hidden behind the app layer that you have to reverse engineer. They’re often listed in the API docs: here are the scopes that this app requires.

You have to capture this consent. This is called trusting on first use. It’s a pretty significant user experience change on the web. Most people before OAuth were just used to name and password dialog boxes. Now you have this new screen that comes up and you have to train users to use. Retraining the internet population is difficult. There are all kinds of users from the tech-savvy young folk to grandparents that aren’t familiar with this flow. It’s a new concept on the web that’s now front and center. Now you have to authorize and bring consent.

The consent can vary based on the application. It can be a time-sensitive range (day, weeks, months), but not all platforms allow you to choose the duration. One thing to watch for when you consent is that the app can do stuff on your behalf - e.g. LinkedIn spamming everyone in your network.

OAuth is an internet-scale solution because it’s per application. You often have the ability to log in to a dashboard to see what applications you’ve given access to and to revoke consent.

OAuth Actors

https://developer.okta.com/blog/2017/06/21/what-the-heck-is-oauth#oauth-actors

The actors in OAuth flows are as follows:

- Resource Owner: owns the data in the resource server. For example, I’m the Resource Owner of my Facebook profile.

- Resource Server: The API which stores data the application wants to access

- Client: the application that wants to access your data

- Authorization Server: The main engine of OAuth

The resource owner is a role that can change with different credentials. It can be an end user, but it can also be a company.

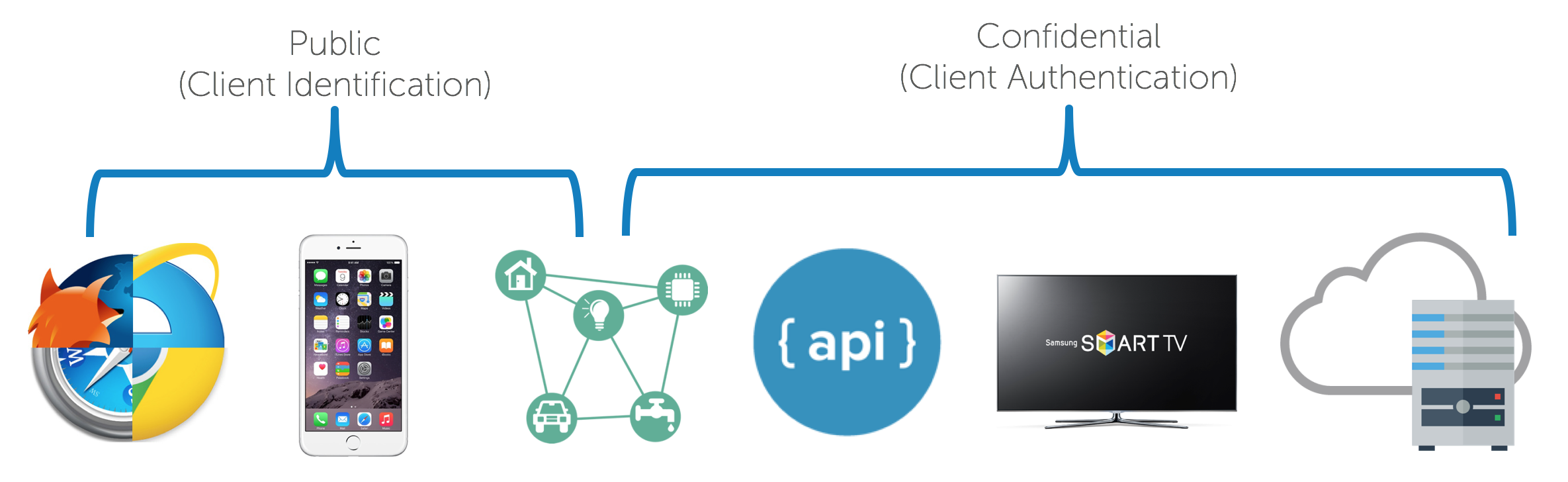

Clients can be public and confidential. There is a significant distinction between the two in OAuth nomenclature. Confidential clients can be trusted to store a secret. They’re not running on a desktop or distributed through an app store. People can’t reverse engineer them and get the secret key. They’re running in a protected area where end users can’t access them.

Public clients are browsers, mobile apps, and IoT devices.

Client registration is also a key component of OAuth. It’s like the DMV of OAuth. You need to get a license plate for your application. This is how your app’s logo shows up in an authorization dialog.

OAuth Tokens

https://developer.okta.com/blog/2017/06/21/what-the-heck-is-oauth#oauth-tokens

Access tokens are the token the client uses to access the Resource Server (API). They’re meant to be short-lived. Think of them in hours and minutes, not days and month. You don’t need a confidential client to get an access token. You can get access tokens with public clients. They’re designed to optimize for internet scale problems. Because these tokens can be short lived and scale out, they can’t be revoked, you just have to wait for them to time out.

The other token is the refresh token. This is much longer-lived; days, months, years. This can be used to get new tokens. To get a refresh token, applications typically require confidential clients with authentication.

Refresh tokens can be revoked. When revoking an application’s access in a dashboard, you’re killing its refresh token. This gives you the ability to force the clients to rotate secrets. What you’re doing is you’re using your refresh token to get new access tokens and the access tokens are going over the wire to hit all the API resources. Each time you refresh your access token you get a new cryptographically signed token. Key rotation is built into the system.

The OAuth spec doesn’t define what a token is. It can be in whatever format you want. Usually though, you want these tokens to be JSON Web Tokens (a standard). In a nutshell, a JWT (pronounced “jot”) is a secure and trustworthy standard for token authentication. JWTs allow you to digitally sign information (referred to as claims) with a signature and can be verified at a later time with a secret signing key.

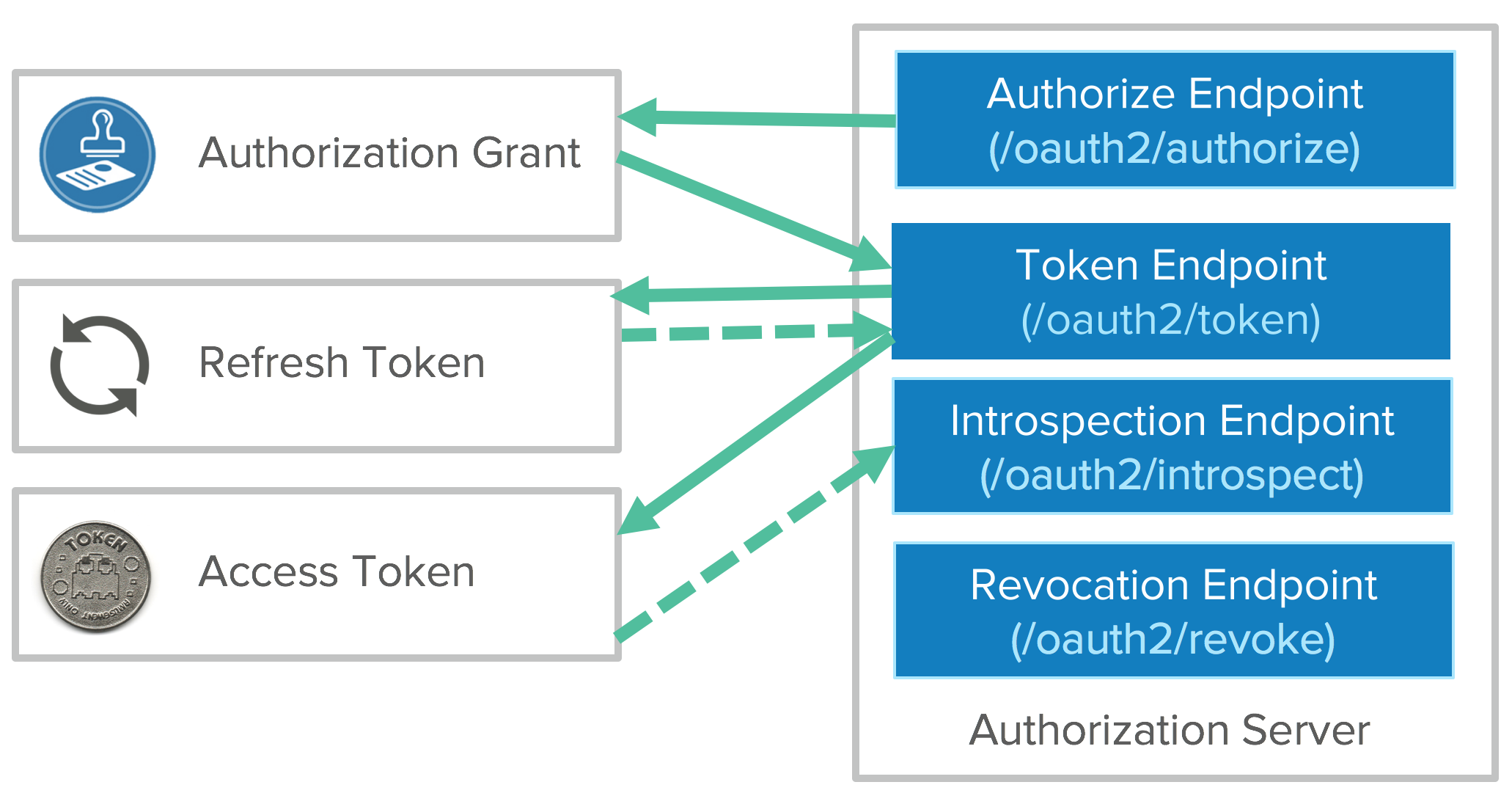

Tokens are retrieved from endpoints on the authorization server. The two main endpoints are the authorize endpoint and the token endpoint. They’re separated for different use cases. The authorize endpoint is where you go to get consent and authorization from the user. This returns an authorization grant that says the user has consented to it. Then the authorization is passed to the token endpoint. The token endpoint processes the grant and says “great, here’s your refresh token and your access token”.

You can use the access token to get access to APIs. Once it expires, you’ll have to go back to the token endpoint with the refresh token to get a new access token.

There’s a pay to play problem here. Getting developers to do OAuth flows increases security, but there’s more friction. There are opportunities for toolkits and platforms to simplify things and help with token management. Luckily, OAuth is pretty mature these days, and chances are your favorite language or framework has tools available to simplify things.

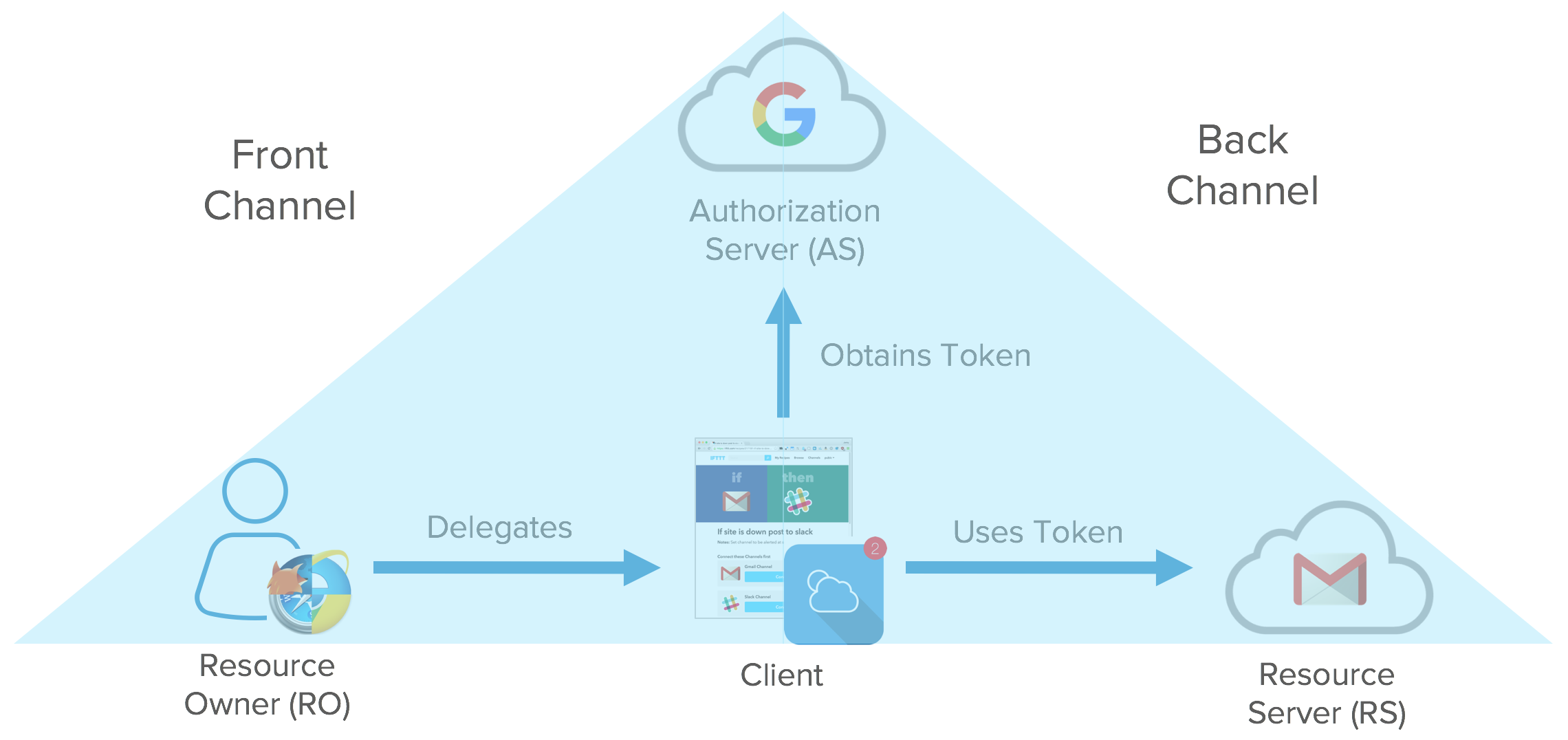

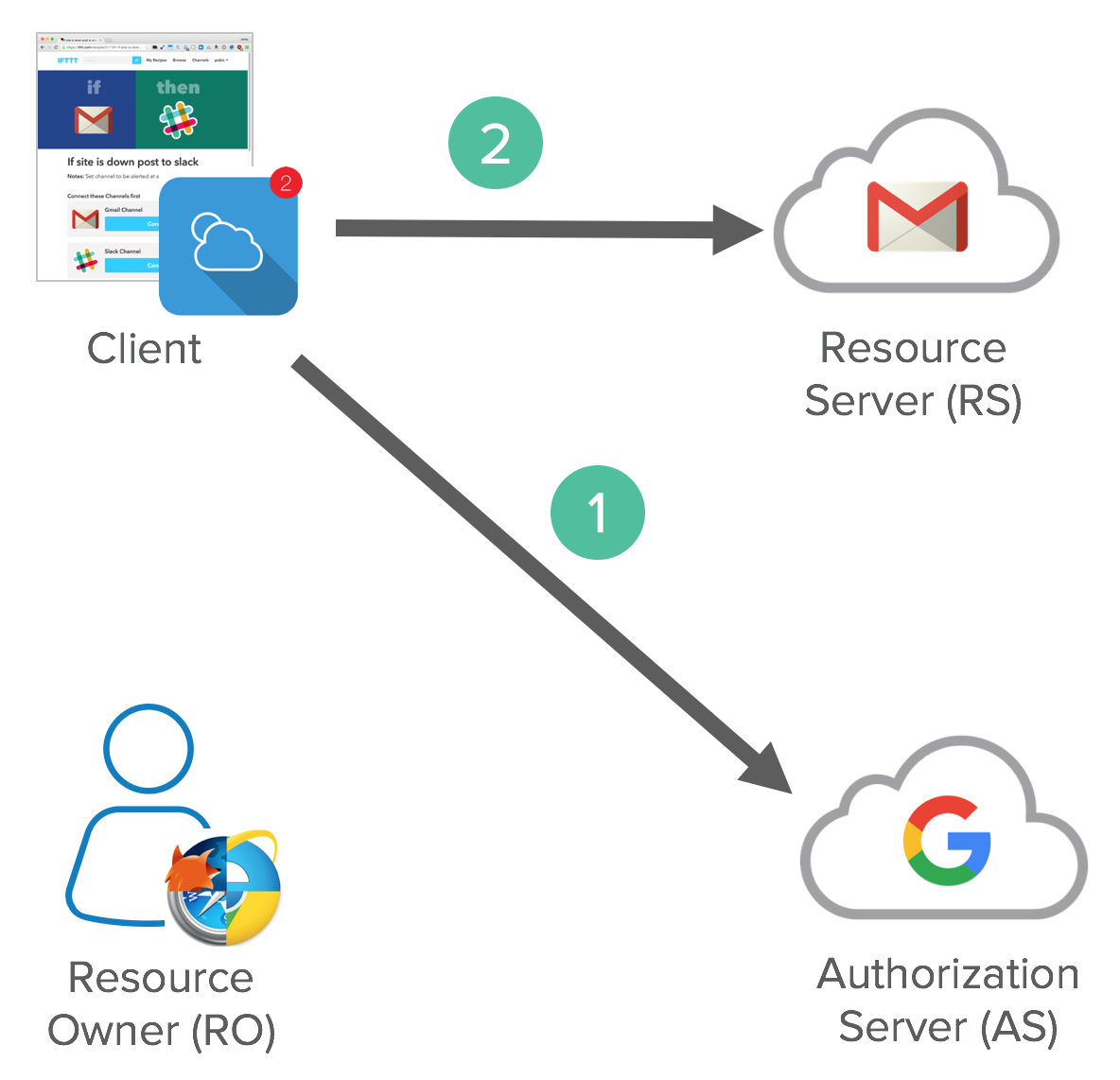

We’ve talked a bit about the client types, the token types, and the endpoints of the authorization server and how we can pass that to a resource server. I mentioned two different flows: getting the authorization and getting the tokens. Those don’t have to happen on the same channel. The front channel is what goes over the browser. The browser redirected the user to the authorization server, the user gave consent. This happens on the user’s browser. Once the user takes that authorization grant and hands that to the application, the client application no longer needs to use the browser to complete the OAuth flow to get the tokens.

The tokens are meant to be consumed by the client application so it can access resources on your behalf. We call that the back channel. The back channel is an HTTP call directly from the client application to the resource server to exchange the authorization grant for tokens. These channels are used for different flows depending on what device capabilities you have.

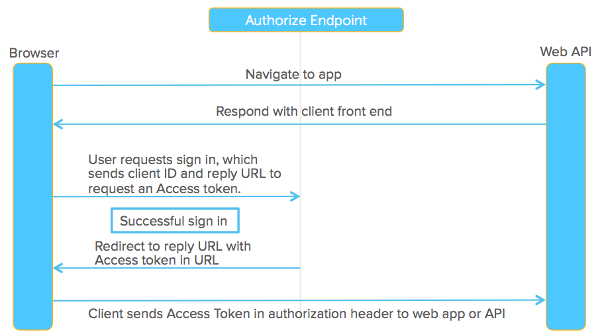

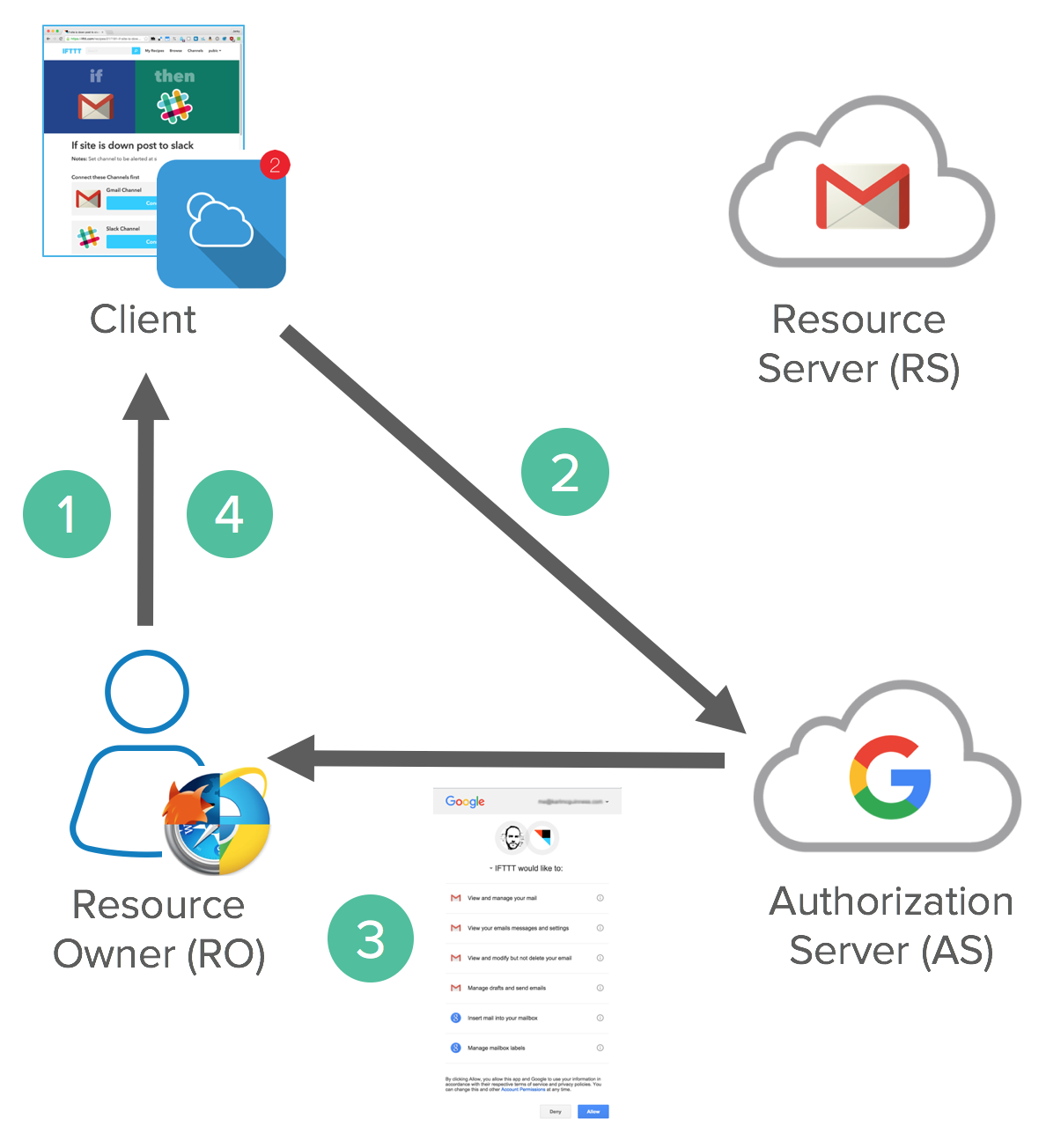

For example, a Front Channel Flow where you authorize via user agent might look as follows:

- Resource Owner starts flow to delegate access to protected resource

- Client sends authorization request with desired scopes via browser redirect to the Authorize Endpoint on the Authorization Server

- Authorization Server returns a consent dialog saying “do you allow this application to have access to these scopes?” Of course, you’ll need to authenticate to the application, so if you’re not authenticated to your Resource Server, it’ll ask you to login. If you already have a cached session cookie, you’ll just see the consent dialog box. View the consent dialog, and agree.

- The authorization grant is passed back to the application via browser redirect. This all happens on the front channel.

There’s also a variance in this flow called the implicit flow. We’ll get to that in a minute.

This is what it looks like on the wire.

Request

GET https://accounts.google.com/o/oauth2/auth?scope=gmail.insert gmail.send

&redirect_uri=https://app.example.com/oauth2/callback

&response_type=code&client_id=812741506391

&state=af0ifjsldkj

This is a GET request with a bunch of query params (not URL-encoded for example purposes). Scopes are from Gmail’s API. The redirect_uri is the URL of the client application that the authorization grant should be returned to. This should match the value from the client registration process (at the DMV). You don’t want the authorization being bounced back to a foreign application. Response type varies the OAuth flows. Client ID is also from the registration process. State is a security flag, similar to XRSF. To learn more about XRSF, see DZone’s “Cross-Site Request Forgery explained” https://dzone.com/articles/cross-site-request-forgery

Response

HTTP/1.1 302 Found

Location: https://app.example.com/oauth2/callback?

code=MsCeLvIaQm6bTrgtp7&state=af0ifjsldkj

The code returned is the authorization grant and state is to ensure it’s not forged and it’s from the same request.

After the Front Channel is done, a Back Channel Flow happens, exchanging the authorization code for an access token.

The Client application sends an access token request to the token endpoint on the Authorization Server with confidential client credentials and client id. This process exchanges an Authorization Code Grant for an Access Token and (optionally) a Refresh Token. Client accesses a protected resource with Access Token.

Below is how this looks in raw HTTP.

Request

POST /oauth2/v3/token HTTP/1.1

Host: www.googleapis.com

Content-Type: application/x-www-form-urlencoded

code=MsCeLvIaQm6bTrgtp7&client_id=812741506391&client_secret={client_secret}&redirect_uri=https://app.example.com/oauth2/callback&grant_type=authorization_code

The grant_type is the extensibility part of OAuth. It’s an authorization code from a precomputed perspective. It opens up the flexibility to have different ways to describe these grants. This is the most common type of OAuth flow.

Response

{

"access_token": "2YotnFZFEjr1zCsicMWpAA",

"token_type": "Bearer",

"expires_in": 3600,

"refresh_token": "tGzv3JOkF0XG5Qx2TlKWIA"

}

The response is JSON. You can be reactive or proactive in using tokens. Proactive is to have a timer in your client. Reactive is to catch an error and attempt to get a new token then.

Once you have an access token, you can use the access token in an Authentication header (using the token_type as a prefix) to make protected resource requests.

curl -H "Authorization: Bearer 2YotnFZFEjr1zCsicMWpAA" \

https://www.googleapis.com/gmail/v1/users/1444587525/messages

So now you have a front channel, a back channel, different endpoints, and different clients. You have to mix and match these for different use cases. This up-levels the complexity of OAuth and it can get confusing.

OAuth Grant Types and Flows

Security and the Enterprise

There’s a large surface area with OAuth. With Implicit Flow, there’s lots of redirects and lots of room for errors. There’s been a lot of people trying to exploit OAuth between applications and it’s easy to do if you don’t follow recommended Web Security 101 guidelines. For example:

- Always use CSRF token with the state parameter to ensure flow integrity

- Always whitelist redirect URIs to ensure proper URI validations

- Bind the same client to authorization grants and token requests with a client ID

- For confidential clients, make sure the client secrets aren’t leaked. Don’t put a client secret in your app that’s distributed through an App Store!

The biggest complaint about OAuth in general comes from Security people. It’s regarding the Bearer tokens and that they can be passed just like session cookies. You can pass it around and you’re good to go, it’s not cryptographically bound to the user. Using JWTs helps because they can’t be tampered with. However, in the end, a JWT is just a string of characters so they can easily be copied and used in an Authorization header.

Enterprise OAuth 2.0 Use Cases

https://developer.okta.com/blog/2017/06/21/what-the-heck-is-oauth#enterprise-oauth-20-use-cases

OAuth decouples your authorization policy decisions from authentication. It enables the right blend of fine and coarse grained authorization. It can replace traditional Web Access Management (WAM) Policies. It’s also great for restricting and revoking permissions when building apps that can access specific APIs. It ensures only managed and/or compliant devices can access specific APIs. It has deep integration with identity deprovisioning workflows to revoke all tokens from a user or device. Finally, it supports federation with an identity provider.

OAuth is not an Authentication Protocol

To summarize some of the misconceptions of OAuth 2.0: it’s not backwards compatible with OAuth 1.0. It replaces signatures with HTTPS for all communication. When people talk about OAuth today, they’re talking about OAuth 2.0.

Because OAuth is an authorization framework and not a protocol, you may have interoperability issues. There are lots of variances in how teams implement OAuth and you might need custom code to integrate with vendors.

OAuth 2.0 is not an authentication protocol. It even says so in its documentation.

https://oauth.net/articles/authentication/

We’ve been talking about delegated authorization this whole time. It’s not about authenticating the user, and this is key. OAuth 2.0 alone says absolutely nothing about the user. You just have a token to get access to a resource.

There’s a huge number of additions that’ve happened to OAuth in the last several years. These add complexity back on top of OAuth to complete a variety of enterprise scenarios. For example, JWTs can be used as interoperable tokens that can be signed and encrypted.

OAuth 2.0 Summary

https://developer.okta.com/blog/2017/06/21/what-the-heck-is-oauth#oauth-20-summary

OAuth 2.0 is an authorization framework for delegated access to APIs. It involves clients that request scopes that Resource Owners authorize/give consent to. Authorization grants are exchanged for access tokens and refresh tokens (depending on flow). There are multiple flows to address varying client and authorization scenarios. JWTs can be used for structured tokens between Authorization Servers and Resource Servers.

OAuth has a very large security surface area. Make sure to use a secure toolkit and validate all inputs!

OAuth is not an authentication protocol. OpenID Connect extends OAuth 2.0 for authentication scenarios and is often called “SAML with curly-braces”. If you’re looking to dive even deeper into OAuth 2.0, I recommend you check out OAuth.com, take Okta’s Auth SDK for a spin, and try out the OAuth flows for yourself.